By Dr Detina Zalli

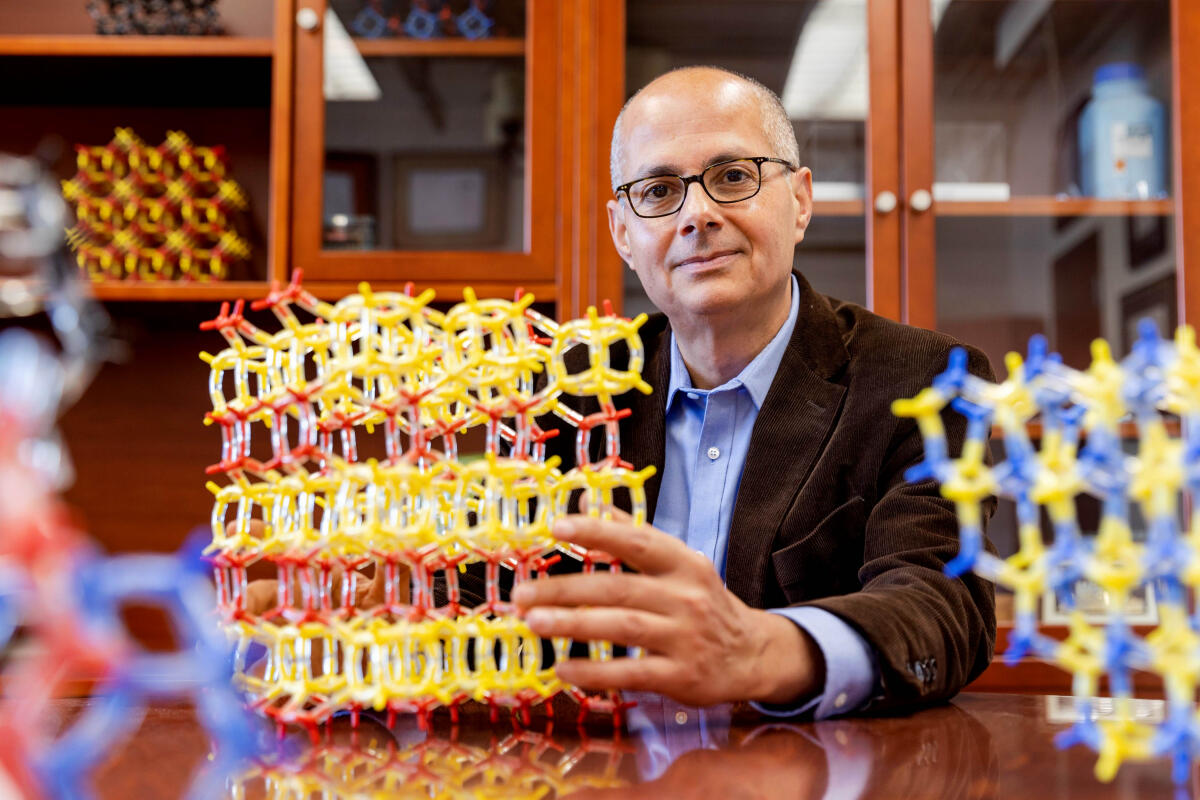

When I read that Professors Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson, and Omar M. Yaghi had won the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the development of metal organic frameworks, I didn’t think of molecules. I thought of survival. I thought of the unseen chemistry that allows a person, or an idea, to hold itself together after being torn apart. Yaghi’s frameworks, so porous that a gram can contain more surface area than a football field, are not only technological marvels. They are metaphors for what it means to live a human life: to build structures that can breathe.

I celebrate all three laureates, but I see something in Yaghi’s story that speaks to something ancient in me. He was born in Amman to Palestinian parents who had fled Gaza. He has spoken about sharing a room with goats, about nights when electricity flickered like an unreliable promise, about learning that curiosity can be rebellion. At fifteen, he left for America with little English and less certainty. Out of that scarcity, he created a science of connection, reticular chemistry, the deliberate stitching together of building blocks to form frameworks so open that light, air, and water can flow through them. His genius was not to fill emptiness, but to structure it.

I cannot presume to know the exact weight of his history. But I recognise the physics of it. I was born in Albania, and I too, fled a collapsing world. I remember the speedboat that carried us across the Adriatic, thirty of us packed into a vessel built for ten. The air stank of petrol, and the sea was so black it erased the horizon. Even the sky felt temporary. Men with guns stood silent. You learn to breathe quietly. You learn that if you scream, you die.

Refuge does not end when the boat lands. It enters your bloodstream. It changes how you react to silence, how you see light. But exile also sharpens the mind. It trains you to notice the invisible bonds that hold things together, the forces that keep collapse at bay. It teaches you structure.

In my professional life, I have been fortunate to teach at some of the world’s great universities – Harvard, Oxford, Imperial College, and Cambridge where I have taught a range of courses, including foundational chemistry for medicine and the biomedical sciences. I teach students about diffusion, membranes, blood gases, and how the body maintains equilibrium through permeability. But what I am really teaching is how life depends on openness. Oxygen crosses a membrane not because the membrane is strong, but because it allows passage. Dialysis saves lives because its barrier is selective, not sealed.

Every lesson in chemistry is also a lesson in ethics. Porosity is not weakness; it is wisdom. It is the discipline of remaining open even when the world demands you close. In molecules, in medicine, and in human lives, the same law applies: connection is survival.

Perhaps that is what all exiles know, consciously or not that emptiness is not an ending but an interval. That absence can be redesigned. The world will always break; the work is to decide how to hold the pieces.

When I think of Yaghi’s frameworks, I see not only atoms aligning across impossible distances, but people doing the same. Families held together by memory and hope, classrooms connected by curiosity, strangers linked by compassion they cannot even explain. Every act of discovery is an act of faith, a refusal to accept the void as final.

I often tell my students that exile is not always geographic. We all experience it in some form- the patient exiled by illness from a former body, the grieving parent exiled from a former world, the anxious person exiled from sleep. Chemistry and compassion share a truth: nothing isolated endures. Whether in the human body or the human spirit, survival is always collaborative.

Professor Yaghi once said that the beauty of chemistry lies in creating order out of emptiness. I think the same is true of being human. His frameworks, like our lives, are held together by invisible forces- delicate, deliberate, resilient. They remind us that openness is not exposure; it is architecture. The same subtle bonds that keep a molecule intact can hold a family, a community, a civilisation.

When I see him standing on the Nobel stage, I don’t just see science rewarded. I see the vindication of every act of endurance – every parent who crossed a sea, every student who studied in another language, every child who waited at a door for a promise to return.

Because the truth is this: we are all frameworks of air and memory. We survive by connection. We endure by permeability. We become human by allowing the world to pass through us without breaking us apart.

And perhaps that is the quiet miracle of existence – that we still breathe, and in breathing, we build.

To Professors Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson, and Omar M. Yaghi and to every person who has ever built a home from nothing.